Selecting data

Let’s begin by learning how to fetch information from it. First of all, PostgreSQL implements the SQL communication standard, that means that you can send commands to PostgreSQL through an SQL-like language. No engine implements the SQL protocol perfectly and PostgreSQL is no exception, it has it’s own flavor of SQL and we’ll learn to use it in the following lessons. Onwards, whenever we use the term SQL it means the PostgreSQL version of SQL instead of the SQL standard.

SQL is a language that allows us to communicate to the PostgreSQL server and request it to do something, in this website we focus on the task of requesting information formatted in a specific manner, so we’ll not cover commands that are used to create, delete or modify data or any database elements like creating tables, users or other. That means that the commands we’ll learn will not modify anything, only return data. Onwards when we refer to a query statement we are referring to the act of requesting PostgreSQL to return some data through a command statement.

To create a query we write commands that are commonly known as clauses. Let’s take a look at a complete query structure:

[with with_expression]

select [distinct] select_expression

from table_expression

join table_expression on join_condition

where where_condition

group by group_expression

having group_condition

window window_expression

order by sort_expression

limit limit_expression

[]means optional

A|Bmeans that you could useAorB

Anything that ends with

_expressionor_conditionmeans that we’ll use a combination of clauses and functions

Anything else is a clause

Seems intimidating, right? As for anything, don’t worry, we’ll go step by step, we just want you to see all that you will learn and for you to be able to track you progress, we recommend that you check this structure after completing a section so you can appreciate all that you have learned so far. Let’s get a quick summary of each clause and in which section will you learn to use it:

WITH: define virtual tables to be used on your final query. We review it on the SUBQUERY section.SELECT: defines what information to return for display. We’ll review it in this section.FROM: establish from what tables or expression will information be fetched. We’ll review it in this section.JOIN: allows rows from different tables and expressions to be appended horizontally and vertically. We review it on the JOIN section.WHERE: creates conditions to filter rows. We review it on the WHERE section.GROUP BY: create groups used to calculate aggregate metrics. We review it on the GROUP and SORT section.HAVING: similar to where but using aggregate conditions. We review it on the GROUP and SORT section.WINDOW: defines common ways of treating data windows. We review it on the WINDOW FUNCTION section.ORDER BY: define how to sort results. We review it on the GROUP and SORT section.LIMIT: restrict the number of rows to return. We’ll review it in this section.

As a caveat, there’re more clauses that we can use like OFFSET, FETCH or FOR but they’re generally not relevant for data analysis purposes so we’ll skip them, but as always, if your curious we encourage you to dive in the PostgreSQL documentation to learn any gaps that are not covered here. Now let’s dive in with the first clause:

SELECT

Let’s start with our first query! The SELECT clause instructs Postgres to return some information. For example, try to execute the following queries in the query editor and check the result:

-- This is a comment, to create one you need to prepend a -- symbol

-- Comments do not execute, they're used to add context

select 1; -- This will return the value 1

select 'Hello World!'; -- This will return a string

select '2024-01-01'::date; -- This will return a date

select true; -- This will return a boolean

select false; -- This will return a boolean

::typeis an operator that converts the values in the left to the type specified. The above example changes the string'2024-01-01'to aDatetype

;is used to delimiter queries, this way Postgres knows thatselect 1andselect 'Hello World!'are actually two different queries. This is important as queries are generally multiline.

SQL is not case sensitive, so SELECT or select (or any other clause) is equivalent

These queries are instructing PostgreSQL to return hardcoded data in a specific format, we’ll see later how to request information from tables or other sources.

Multiple columns

SELECT results are tables that may contain multiple rows and columns, the above examples only requests 1 column and 1 row but we can expand it easily using the , delimiter:

-- This will return 1 row and three columns

select 1, 'Hello World!', '2024-01-01'::date;

-- We can add column names using the AS operator

-- If we want a column name to contain spaces we have to encode it with double quotes

select 1 as column_1, 'Hello World!' as "Column 2";

-- As it's common in programming, they're usually multiple ways to achieve something

-- For renaming columns, we can skip the AS keyword an it will still work

select 1 column_1, 'Hello World!' "Column 2";Note that string values are encoded in

'quotes and column names are encoded in"names. This is a common source of bugs

Once you defined a specific column name, you’ll have to use it for any other operation, if you try to use the previous column name then PostgreSQL will fail. This will be evident on the WHERE section

Multiple rows

We can append the results of multiple queries to include more rows in your response by using the UNION clause:

-- This will return 3 rows and 3 columns

select 1, 'Hello World!', '2024-01-01'::date

union

select 2, 'Goodbye World!', '2024-01-02'::date

union

select 3, 'Hello again!', '2024-01-03'::dateWhen using

UNION, make sure that the column types and column names are the same, if not Postgres could force a type conversion to string, or return an error when it cannot force the conversion

NULL

In any data setting having missing information is common, just think of the last time that you filled a form, you might have not completed every requested field. Missing information on a field is represented by the NULL value:

-- If you execute this snippet, you'll see a null in the middle of the result table

select 1, 'Hello World!', '2024-01-01'::date

union

select 2, NULL, '2024-01-02'::date

union

select 3, 'Hello again!', '2024-01-03'::dateFunctions

SQL allows us to transform data or execute complex logic through the use of functions. These can be called using the functions name and passing arguments with the syntax function_name(arg1, arg2, ...). Let’s run some examples:

-- The round function takes the 5.35 input and rounds i to the nearest integer

select round(5.35); -- 5

-- Functions often can take multiple arguments, for example round can accept a

-- second argument specifying the number of decimals to be rounded

select round(5.3589, 2); -- 5.36

-- left(text, n) is used to extract the n characters starting from the left

select left('Hello', 3); -- 'Hel'

-- Some special functions can be used without the () syntax

select 1 + 2; -- 3, the + function can be used mathematicallyPostgreSQL has a vast collection of functions and we cannot hope to include all of them in this documentation. As always, the best place to study is the documentation, but we’ll leave some examples of common day-to-day functions you may need:

Math functions

select 1 + 1; -- Addition --> 2

select 1 - 1; -- Subtraction --> 0

select 2 * 3; -- Multiplication --> 6

select 4 / 2; -- Division --> 2

select 3 % 2; -- Module --> 1

select abs(-5); -- Absolute value --> 5

select trunc(4.9); -- Truncate to the lowest integer --> 4String functions

select 'Hello' || ' World'; -- Concatenate strings --> 'Hello World'

select right('Hello', 3); -- Same as left but starting from the right --> 'llo'

-- Select from the first character to the third

select substring('Hello', 1, 3); -- 'Hel'

select char_length('Hello'); -- Calculate the number of characters --> 5

select upper('Hello'); -- Convert to uppercase --> 'HELLO'

select lower('Hello'); -- Convert to lowercase --> 'hello'

-- Remove leading and final spaces, also remove change double or more spaces to 1 space

select trim(' Hello world '); -- 'Hello world'

-- Check if the a string is inside another string

select 'Hello World' ilike '%wor%' -- trueBoolean functions

-- The = operator checks that both statements are the same

select 5 = 5; -- True

-- The != operator checks that the statements are not equal

select 5 != 5; -- False

select 5 > 4; -- True

select 5 > 5; -- False

select 4 >= 4; -- True

select 4 < 4; -- False

select 4 <= 4; -- True

-- AND checks that the left and right statements are true

select true and true; -- True

select 5 = 5 and 5 != 5; -- False --> Think why

-- OR checks that at least on of the statements is true

select 5 = 5 or 5 != 5; -- True

-- AND as priority over OR, so use parenthesis to be explicit

select true and true or true and false; -- Is the same as:

select (true and true) or (true and false);

-- Check if a value is NULL or not

select 1 is NULL; -- This returns false because 1 is not a NULL value

select 1 is NOT NULL; -- This returns true because 1 is not a NULL valueDate functions

PostgreSQL supports multiple date types:

DATE: it includes the year, month and day. It does not include the timezone.TIME: it only includes the hour and second. It’s 24 hour so you also have get the AM or PM indicator. It does not include the timezone.TIMESTAMP: it includes the year, month, day, hour, second and millisecond. It does not include the timezone.TIMESTAMPTZ: it’s the same as aTIMESTAMPincluding the timezone.INTERVAL: it’s a duration and can contain from century, decade, year, month, day, hour, minute, second and milliseconds.

-- Returns the current time using the timezone specified in the server (generally it's set to UTC)

select current_time;

-- To force a timezone we can use the at time zone clause

select current_time at time zone 'America/Mexico_City';

-- Return the current date using the timezone specified in the server

-- You can also use the at time zone clause if required

select current_date;

-- This returns the current timestamp with timezone

select now();

-- This returns the current day as a date from the current timestamp

select date_trunc('day', now());

-- This returns the current month as a date, this means that the day will be set to the first day of the month

select date_trunc('month', now());

-- This returns the current year as a date, this means that the day and month will be set to the first day of the year

select date_trunc('year', now());

-- This returns the current minute as a timestamp, converting the seconds and milliseconds to 0

select date_trunc('minute', now());

-- Usually timestamps in databases are set to a specific time zone, but sometimes it's not set so the user needs to specify it in the query

select '2023-05-01T10:00:00'::timestamp at time zone 'UTC';

select '2023-05-01T10:00:00'::timestamp at time zone 'America/Mexico_City';

-- Extract a particular date part

select extract(century from timestamp '2000-12-16 12:21:13'); -- 20

select extract(day from interval '40 days 1 minute'); -- 40

-- You can add dates intervals to a date

select '2022-01-01'::date + interval '1 year'; -- '2023-01-01'

-- Check if a date is before then another one

select '2022-01-01'::date > '2021-01-01'::date; -- TrueThere are much more functions and operations that you can do with dates, we encourage you to check the official documentation.

Conditionals

PostgreSQL allows us to use conditional logic that are similar to IF ELSE logic using the CASE clause:

- You have to define

WHENstatement that check if a condition returns a true boolean - If the

WHENstatements returns a true value, theCASEclause will return what’s specified after theTHENclause - If false, it will go to the next

WHENstatement and repeat the process until it ends (in which case theCASEstatement will returnNULL), or will return what’s specified in theELSEstatement (think of it like the fallback) - Finally include an

ENDclause to close theCASEstatement

Let’s see some examples:

-- This returns 1

select case when true then 1 else 0 end;

-- This returns 0

select case when 5 != 5 then 1 else 0 end;

-- This returns 4

select

case

when 5 != 5 then 1

when 5 = 5 then 2 * 2

else 0

end;

-- This returns NULL

select case when false then 1 end;Another conditional function that is commonly used is coalesce. This function receives multiple arguments and returns the first result (starting from the left side) that is NOT NULL, and will return NULL if all arguments are NULL:

-- This returns 2

select coalesce(NULL, NULL, 2, 3);

-- This returns NULL

select coalesce(NULL, NULL);Select from a specific table

Until now we’re getting you used to the SELECT statement and we’re only working with hardcoded data, but the fun part starts now, let’s get data directly from a table, for that we’ll need to use the FROM clause:

select * from "Track"

*is a wildcard that means everything

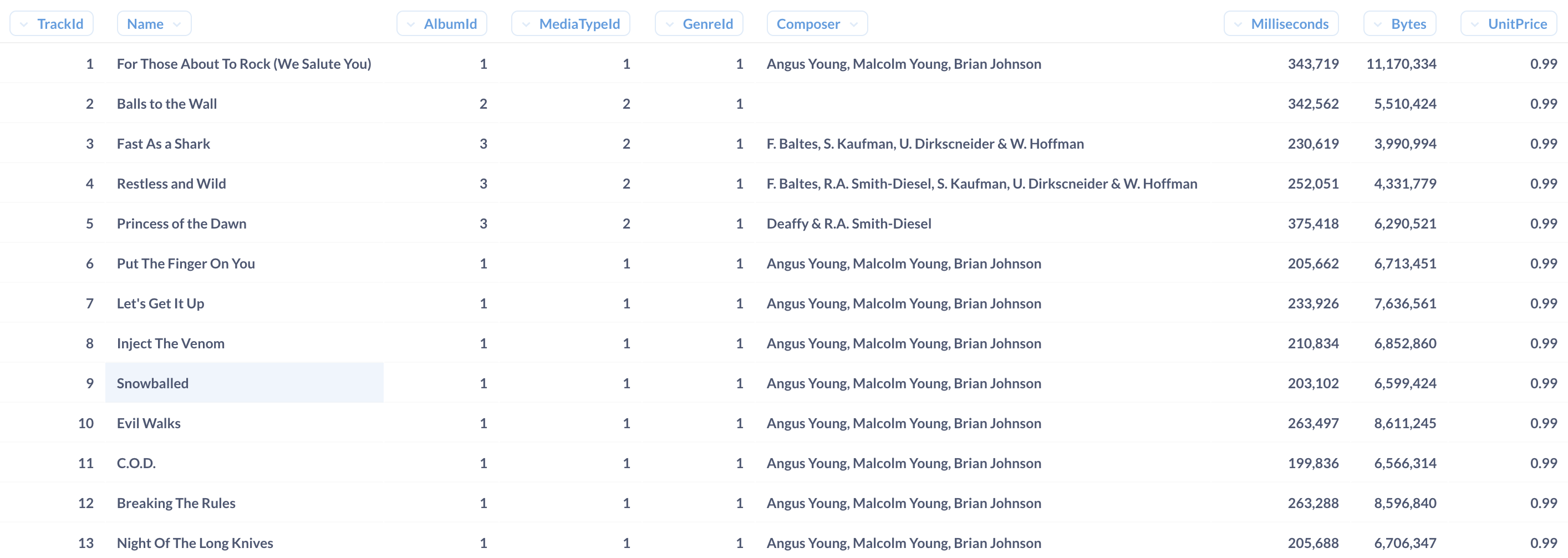

The above query should return something like:

FROM "Track" request postgres to access the "Track" table, and SELECT * request postgres to return all columns of the table. We request specific columns to be returned in the SELECT statement:

-- This only returns three columns

select

-- We still can change column names

"Name" as "Track Name",

-- We also can use functions and pass data from one or multiple columns as arguments

char_length("Name") as "Track Name length",

-- As we saw, you can skip the AS clause to define a column name

"UnitPrice" "Price"

from "Track"Schemas

Tables in PostgreSQL are stored in Schemas, think of it like a folder that contains multiple tables, views and other elements that we use to organize our data. The default schema is generally called public and we don’t need to specify it in the FROM clause, but we still can do it using the . notation:

select * from public."Track"This is not so useful for the default schema but is important if you want to reference other schemas:

select t.ticket_no from bookings.tickets as tTables also can be named using the

ASkeyword, and referenced using the.notation as with schemas. This will be particularly important when we arrive to theJOINclause and work with multiple tables

Depending on how table and column names were created, it may be necessary to use double quotes

""to call them. In particular this public schema requires us to use""to call tables and columns, but the bookings schema does not require it (although you could still use it if you wanted). This setting depends on how the engineers configured the database

Select from a Set Returning Function

Some functions let you create virtual tables that can be selected from, for example, the generate_series function let’s you create a sequence of dates, timestamps or numbers:

select

dates.* -- This only returns a single column, you could even call it with dates without using the .* notation

from generate_series(

now(), -- Initial timestamp

now() + interval '5 month', -- End timestamp (inclusive)

interval '1 day' -- Steps

) as datesThe above snippet will create a table with 1 column and as many rows as days in the next 5 months. To generate a numeric sequence you could use:

select

numbers.*

from generate_series(

1.4, -- Initial number

2.3, -- End number (inclusive)

0.1 -- Steps

) as numbersAggregate functions

Until know we have returned all rows from a table, but we also have functions that will only return an aggregated single row, for example we may want to count the number of rows in a table. These are called aggregated functions and are useful to return transformation across multiple rows. Let’s see some examples:

-- This returns a single row that gives us the number of rows in the tracks table

select count(*) from "Track";

-- This sums up all of the prices in the track

select sum("UnitPrice") from "Track";

-- This calculates the average of the prices

select avg("UnitPrice") from "Track";

-- This creates a single array that contains all of the elements of the original column

-- We can extract elements of the array by using a subscript (starts from 1)

select

array_agg(aircraft_code),

(array_agg(aircraft_code))[1], -- First element of the array

(array_agg(aircraft_code))[array_length(array_agg(aircraft_code), 1)] -- Last element of the array

from bookings.aircrafts;

-- Instead of an array, return a string that contains all of the elements separated by a specified separator

-- This returns all codes in a single string separated by spaces

select string_agg(aircraft_code, ' ') from bookings.aircrafts;

-- This checks that all prices are above 0.5, if so it will return true, if not false

select bool_and("UnitPrice" > 0.5) from "Track";

-- This checks that at least 1 price is above 0.5, if so it will return true, if not false

select bool_or("UnitPrice" > 0.5) from "Track"; Because aggregate functions forces a single row result, our SELECT statement must return 1 single row for every column that we specify. The following example does not work because the count function wants to return 1 row, but the "UnitPrice" statement would return multiple rows:

select count(*), "UnitPrice" from "Track"That does not mean that we cannot combine normal functions with aggregate functions, but we need to put the aggregate functions as the outer function, so it always return 1 row. The following example works because we transform "Milliseconds" into seconds but dividing it by 1000, and later summing it up to only return 1 row:

select count(*), sum("Milliseconds" / 1000) from "Track"Unnest

We have seen how arrays are collections of other data types like text, numbers or others. In some occasions we want to work with the elements of the array as if they were in their own row, so we can use the set generating function of unnest:

select unnest(string_to_array("Composer", ','))

from "Track"The string_to_array takes the "Composer" text and creates an array of composers separated by a ,. After that, unnest creates a row for each element of the array.

Unique values

Data from tables can be repeated, for example "Track" table has a "UnitPrice" column that for most songs is the same, if we only want to see the unique "UnitPrice" values we can use theDISTINCT` clause:

-- This will only return the different tracks that we have

select distinct "UnitPrice" from "Track"

-- Some functions allows us to use the distinct clause inside it's arguments

-- this will create an array but won't repeat aircraft codes

select array_agg(distinct aircraft_code) from bookings.aircrafts;It’s generally preferable to use

GROUPinstead ofDISTINCT, we’ll see this on the GROUP and SORT section

Limit results

Use the LIMIT keyword to limit the number of rows to be returned, which is very useful for big tables or exploratory analysis like when we only want some to check some sample table data without having to scan the entire table.

-- Limit the result table to 10 rows

select "Name" from "Track" limit 10Generally your PostgreSQL client already has a built in LIMIT value that is always enforced, for example Metabase and the query editor always limits results up to 2000 rows, if you want more rows you’ll need to export the results into a file (like Excel, CSV or JSON). Other tools like DBeaver enforces 200 row limits only in the case where you don’t explicitly state a LIMIT statement, but will comply with your LIMIT statement if specified.

Exercises

Congratulations for finishing your first section! After each section we propose a set of exercises to test your learnings, we firmly believe that applying recently learned concepts is a great recipe to generate long lasting memories and to really understand concepts (or to nudge you on concepts that you may have missed or not understand really). We highly encourage you to try to solve the exercises before moving into the next section, as each section builds itself on the knowledge of past sections.

Solve them in the query editor.

- Fetch the

"Track"table and create a column that shows the track duration as anINTERVALtype, limit the result to 1000 rows (hint: check the functionmake_interval) - Fetch the

"Track"table and return the following columns (hint: check the functionstring_to_arrayandarray_length):- Track name

- Track composers

- Number of composers

- Name of the first composer

- Name of the last composer (if there is only 1 composer, then return NULL)

- Fix the following query:

select 1, 'Hello World!', '2024-01-01'::date

union

select 'Hello World!', NULL, '2024-01-02'::date

union

select 3, 'Hello again!', '2024-01-32'::date- Fetch the

"Employee"table and create a column that outputs the following pattern:(General Manager) Adams, Andrew. Born on Edmonton, AB, Canada. Hired in Aug 02. - How many countries exists in the

"Customer"table? - What’s the average sales per invoice found on the

"Invoice"table? - Generate a time series starting from today until 10 years ago using 1 month-step and format the result as

22 of Sep-1922 --> Odd year? Yes, Odd month? No. - Investigate the differences between

UNION,UNION ALL,INTERSECT.

If you have any difficulty, remember to follow the getting help steps.